Home » Jazz Articles » Building a Jazz Library » Ten Terrific Sax Plus Organ Combinations

Ten Terrific Sax Plus Organ Combinations

Ben Webster

Ben Webster Big Ben Time!

"My One And Only Love"

Fontana North/Universal

1967

Ben Webster is a fundamental figure in jazz history for several reasons. Perhaps the best known is his success in establishing himself as the most refined—and influential—Swing Era's tenor saxophone stylist. His is the silkiest, warmest and deeply sensual sound among the tenor men of his generation, particularly when it comes to ballads, and his Janus-faced transformation in medium and up-tempo numbers is renowned. In this humble yet formidable rendition of "My One and Only Love" his seductive smoothness pairs with Alan Haven, a British organist who created his own instrumental model and notably worked on various James Bond soundtracks. Together, they dispense a wisely restrained declaration of love, steering clear of the cloying sweetness that has undermined many otherwise promising intentions. Rather than an impassioned manifesto, we witness a mature acknowledgment following a long, complex and sometimes painful shared journey. Webster delicately breathes into each carefully chosen note of his loving argument, reserving a small dose of tension for the bridge, while Haven plays thoughtfully with the melody, finding motifs that lead to brief but brilliant reflections at the end of his solo. The second bridge brings again touches of moderate fervor that, nevertheless, lead to a crystal-clear conclusion, emphasized by serene pauses.

Jimmy Smith

Jimmy SmithJimmy Smith At The Organ, Volume 1

"Summertime"

Blue Note Records

1957

Like Webster, Jimmy Smith stands among the elite musicians who revolutionized their instrument's sound or syntax. His impact on performance style remains colossal, with his fingerprints still visible in countless later organists' approaches. Smith mostly embraced the organ-guitar-drums trio format so much appreciated by many of his soul-jazz colleagues, but he also signed many collaborations in a quartet or quintet setting with saxophonists, especially Percy France, Lou Donaldson and Stanley Turrentine. With these notorious sax men, he always sought the perfect opportunity to engage in stimulating musical dialogues, as exemplified by this distinctive "Summertime," where Smith kicks things off with a cadenced pedal motif. A refined Donaldson appears from above, working his instrument's upper register in the exposition, then making a concise speech that ends with bebop resonances. Smith, for his part, takes his playing to another level: much like Stan Getz and Lou Levy's reading two years previous on West Coast Jazz, or John Coltrane and McCoy Tyner's later version on My Favorite Things, the Philadelphia master unleashes a brilliant, imaginative aria that brings a highly disruptive multi-layered harmonic approach to George Gershwin's evergreen standard. The result still sounds contemporary nearly seventy years later, but long before then, players such as Amina Claudine Myers, among many others, had already taken note of its innovations.

Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis / Shirley Scott

Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis / Shirley ScottCookin' with Jaws and the Queen: The Legendary Prestige Cookbook Albums

"My Old Flame"

Craft Recordings

2023

Few mainstream tenor sax players have been swallowed by media obscurity quite like Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis. He was another consummate stylist who, building on the teachings of masters like Webster and Coleman Hawkins, refined an unmistakable language and sound within The Count Basie Orchestra. His partnership with organist Shirley Scott reflects one of his moments of glory, both interpretively and commercially. In this highly suggestive song, Davis reveals himself as mellifluous and conversational, with an almost palpable discourse that gives way to Scott. The so-called "Queen of the Organ" shines greater in her comping than in a solo built, as was her custom, through rushed block chords. Jerome Richardson freshens the room with a pleasant flute interlude, and Davis concludes with velvety mastery, loaded with Hawkins' primordial echoes.

Illinois Jacquet / Wild Bill Davis

Illinois Jacquet / Wild Bill Davis Illinois Jacquet & Wild Bill Davis

"The Man I Love"

Black & Blue

1986

The ultimate "Texas tenor" sound's exponent, Illinois Jacquet's vast influence (not only in jazz) is evident in the already mentioned "Lockjaw" Davis, but also in post-loft combos like Roots and current luminaries, including our last guest, surnamed Carter. A pioneer of high-register harmonics, his expressive signatures and powerful quality shone in orchestras like those of Lionel Hampton and Count Basie, as well as in that mainstream jazz encyclopedia known as Norman Granz's JATP. Active until his final days, in the first half of the '90s he collaborated with the outstanding organist and multi-instrumentalist Joey DeFrancesco, who tragically passed away prematurely. On this swinging and unusually up-tempo "The Man I Love," Jacquet joins Wild Bill Davis, who pioneered popularizing the Hammond organ in jazz, something already tentatively introduced by Fats Waller and Count Basie. The Louisiana native evolves with bold inventiveness through a long development, followed by an equally energetic and strongly rhythmic Davis, before joining Al Bartee's forceful drums and going all together to four. Finally, the spotlight returns to Jacquet, who authoritatively caps off this extended, exhilarating reading of another timeless Gershwin brothers' standard.

David Murray

David MurrayShakill's Warrior

"In The Spirit"

DIW

1991

David Murray's recorded collaborations with Don Pullen span several decades: from the primary, highly combative sessions recorded in the '70s, during the height of loft jazz, to the early '90s with an electric quartet that produced two recordings under the common denominator of Shakill's. From the first of these arises a spiritual that, through its title and the interpretations that give it essence, leaves no doubt about its otherworldly nature. Murray defines the ethereal melody with extreme sensitivity at a larghissimo tempo, then hands it over to Pullen who declaims a heartfelt preaching, almost entirely in a single line, without employing any other instrument's registers except the pedals to mark the bass line: the introspection is such that in numerous moments one can hear (excellent recording by Jim Anderson) the keys' brushing. Murray picks up the gauntlet with an equally magnificent rendition, unusually restrained for him, with a limpid tonal use in the high register which mostly avoids his customary accentuations with harmonics. The melody is presented again, and the piece concludes with a mystical melodic ascension that descends to earthliness in its final moments.

Hamiet Bluiett / D.D. Jackson / Kahil El'Zabar

Hamiet Bluiett / D.D. Jackson / Kahil El'ZabarThe Calling

"Blues Grind"

Soul Note

2001

Also emerging from the loft scene, Hamiet Bluiett stands as one of the baritone saxophone giants, where his mastery (with unprecedented control of five octaves across its sonic range) has lived on through a handful of later performers, as Carlo Actis Dato, Lauren Sevian, Alex Harding, Celine Bonacina, et al. Undoubtedly, if his style of aboriginal sounds—in his own words—had leaned towards modern mainstream or the normal world-music fusion paths, rather than towards free jazz and avant-garde, his name would be more widely recognized. Bluiett showcases his prodigious multi-instrumentalism across a diverse discography as a leader or in collaborative ensembles, as in this trio shared with Ottawa-born pianist and composer D.D. Jackson and Chicago percussionist Kahil El'Zabar. With them, he gives out this adhesive "Blues Grind," a joyously dislocated "Blues March" contrafact kind of, composed by Jackson. Bluiett colors it with his acidic tone, employing those sarcastic off-keys he so cherishes. Jackson surprises us with a performance that turns almost schizophrenic in its second half, with traces of a certain Keith (surnamed Emerson). Then it's time for Bluiett, who with a paroxysmal urgency that does not admit middle ground quickly brings his statement to the boiling point, Jackson's organ and El'Zabar's martial drumming efficiently supporting. After a robust intervention by the latter, the main motif reappears, with Jackson now on piano, ending in a lethal Bluiett's high note capable of piercing the most sensitive eardrums.

Jan Garbarek

Jan Garbarek Places

"Going Places"

ECM Records

1978

At the sonic, stylistic, and media antipodes of Bluiett, Jan Garbarek—who in his beginnings also cultivated thorny free jazz—establishes with his pearly-toned saxophones one of the most notable contemporary sound paradigms, comparable to Miles Davis's muted trumpet or Pat Metheny's synthesized guitar. Two years before his widely criticized Aftenland (ECM Records, 1981), an anesthetic duet between his volatile saxophones and an underutilized pipe organ, Garbarek previewed his taste for this instrument's tonalities in the above-depicted album. This was a far more evocative recording, incorporating the British keyboardist John Taylor, a musician highly regarded by European jazz giants like John Surman and Kenny Wheeler. "Going Places" benefits from the second zero of Jack DeJohnette's nervous accents, which convey that sense of constant movement suggested by the track's name. His drumming supports a melody whose appeal stems from a simple, fragile motif outlined by a soprano sax, modulated by Taylor's cosmic chords and shrewd organ pedal work. Bill Connors' acoustic guitar contrasts with its earthly immediacy against the vast sidereal landscapes traced by the band, while Taylor soberly delivers an intriguing discourse backed by a ceaselessly propulsive DeJohnette. In the final section of this extensive piece, Garbarek and Taylor (now at the piano) enter into other atmospheres. First, they set an almost pastoral mood, followed by an alarming dose of tension. Despite these unexpected turbulences, the journey from the Norwegian fjords to the Sea of Tranquility concludes with a soft lunar landing.

John Surman / Howard Moody

John Surman / Howard MoodyRain On The Window

"Pax Vobiscum"

ECM Records

2009

John Surman, much like Garbarek, is one of those pivotal figures who has been decisive in shaping the ECM's distinctive sound. However, his essential— and extensive—body of work goes beyond a single record label. A baritone saxophone virtuoso like Bluiett, the two share a voracious multi-instrumentalism and stylistically fierce beginnings. Both also acknowledge the determining influence of Harry Carney and, during their respective youths, radically rewrote their primary instrument's language, exploring its sonorous possibilities and pushing its high register to the most extreme pitch altitudes. Despite divergent musical trajectories, Surman and Bluiett share a penchant for abstraction and avant-garde experimentation, combined with more down-to-earth genres—blues and ethnic music for the American, and European folk or religious music for the Tavistock native. Howard Moody, a keyboardist, opera composer, and conductor, belongs to a different musical realm. Though not inherently a jazz musician, his interest in improvised music has led to numerous live collaborations with Surman, whose previous recordings frequently featured saxophone or bass clarinet paired with imposing organ sounds, often electronically generated by himself. None of them exudes the overwhelming pathos of this majestic, cathedral-like "Pax Vobiscum" (Peace be with you). In this cut, the baritone proclaims his message with rising fervor, dramatically supported by the bone-chilling sonority of Moody's pipe organ, which seems to come out from a dark crypt only to progressively illuminate and culminate, in the final bars, amidst a blinding ecstasy.

Noël Balen

Noël BalenMingus Erectus

"Goodbye Pork Pie Hat (In The Church)"

Le Castor Astral

2016

Seasoned with the Duke Ellington Orchestra in the mid-70s and associated with Charles Mingus' final bands and their subsequent reincarnations and sequels, Ricky Ford belongs to that contingent of sensational tenors who, despite carving out a distinctive language and notable discography, remain frustratingly unrecognized by the broader jazz public. Highly active in the '80s and early '90s, Ford drastically reduced his recordings from the 2000s onwards—a development that, given his enormous performative stature, represents a genuine artistic loss. One such isolated intervention is included in a unique tribute project to Mingus by French writer and musician Noël Balen, a limited edition CD book featuring a good portion of the Francophone jazz's who's-who. Here, Ford voices an impressive, almost creepy "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat (In The Church)" alongside French organist Emmanuel Bex, son of a classical pianist. The track's production begins with Ford's initial countdown and intake of breath and—almost—closes with the unnecessary final query about the take's validity, followed by his congratulation. Between these two opposite ends, the saxophonist sketches that perennial marvelous melody, masterfully harmonized by Bex, who at certain moments nearly expels the listener from the room: such is the corporeality of a sound penetrating every corner of occupied space. Ford returns, displaying his art through a peremptory yet wonderfully reasoned solo, his voice thick and varnished, aged across decades among noble reeds and brass. Both musicians reclaim the melody, concluding with a magnificent epilogue whose solemnity is unexpectedly counterbalanced by an ambient recording that summons the listener to return from the afterlife.

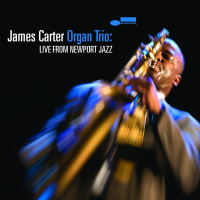

James Carter Organ Trio

James Carter Organ TrioLive From Newport Jazz

"Pour Que Ma Vie Demeure"

Blue Note Records

2019

James Carter emerged as a spectacular sideman in prestigious late 20th-century post-loft and avant-garde ensembles, marking his arrival with two technically and stylistically stunning debut albums in 1994. However, after the mid-'90s, his trajectory gradually settled into a sometimes quite disappointing conventionality. While remaining highly competent, he favored being comfortably situated within the broad eclecticism of modern mainstream jazz. This was reasonable, given the difficulty of meeting the towering expectations his first works had created, and perhaps also foreseeable, considering his transition from a relatively modest, experimentally-inclined Japanese label to an American imprint owned by a massive multinational corporation. Still, in his first albums of the '20s, Carter delves back into radical experimentation.

"Pour Que Ma Vie Demeure" is a song composed and recorded by Django Reinhardt in 1947 and thus carries some inevitable retro qualities, which Carter's organ trio—one of his most exciting projects of recent years—fruitfully updates. His tenor opens the party with an expressiveness that evokes a silent film actor more than a musician whose beginnings were often anchored in the most abstruse avant-garde—a seeming contradiction that has become his hallmark and which enhances his charm. He employs his signature technical arsenal sparingly and is followed by Gerald Gibbs (a musician, like the whole trio, originally from Detroit), who gives a very measured organ statement with fleeting touches of harmonic character. The leader then returns on soprano, becoming progressively uninhibited, as the ensemble builds toward a tremendous finale in which Carter simultaneously challenges the boundaries of his instrument and human auditory perception, delivering a performance that is both technically prodigious and musically compelling.

Tags

Building a Jazz Library

James Carter Organ Trio

Artur Moral

Spain

Barcelona

Big Ben Time!

Fontana North/Universal

ben webster

Alan Haven

Jimmy Smith At The Organ, Volume 1

Blue Note Records

Percy France

Lou Donaldson

Stanley Turrentine

Stan Getz

Lou Levy

West Coast Jazz

John Coltrane

McCoy Tyner

My Favorite Things

Philadelphia

George Gershwin

Amina Claudine Myers

Cookin' with Jaws and the Queen: The Legendary Prestige Cookbook Albums

Craft Recordings

Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis

Coleman Hawkins

The Count Basie Orchestra

Shirley Scott

Jerome Richardson

Illinois Jacquet & Wild Bill Davis

Black & Blue

Illinois Jacquet

Lionel Hampton

Count Basie

Norman Granz

JATP

Joey DeFrancesco

Wild Bill Davis

Fats Waller

Louisiana

Shakill's Warrior

DIW

David Murray

Don Pullen

The Calling

Soul Note

Hamiet Bluiett

Carlo Actis Dato

Lauren Sevian

Alex Harding

Céline Bonacina

Ottawa

D.D. Jackson

Chicago

Kahil El'Zabar

Places

ECM Records

pat metheny

Aftenland

John Taylor

John Surman

Bill Connors

Rain On The Window

Harry Carney

Mingus Erectus

Le Castor Astral

duke ellington

Charles Mingus

Ricky Ford

Noël Balen

Emmanuel Bex

Live From Newport Jazz

James Carter

Django Reinhardt

Gerald Gibbs

Michigan

Comments

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.