Home » Jazz Articles » Profile » Ahmad Jamal: An American Classic

Ahmad Jamal: An American Classic

We achieved the ultimate success... I mean, we were selling so many records at one time, on the original At The Pershing album, that Leonard himself, the president, was in the stockroom shipping with the stock boys.

—Ahmad Jamal

1930-1958: From Pittsburgh to The Pershing

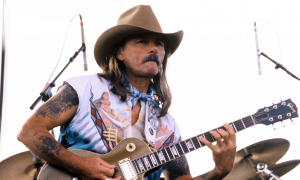

Frederick Russell Jones was born on July 2, 1930, to a working-class family in Pittsburgh. His friends called him Fritz. As a boy, he delivered newspapers to Billy Strayhorn's family. He converted to Islam around 1950 and took the name Ahmad Jamal.His family identified him as a child prodigy at the tender age of three after his uncle challenged him to repeat what he played on the family piano.

Jamal attended Pittsburgh's integrated George Westinghouse High School under the tutelage of musical director Carl McVicker Sr., where he studied classical music as well as jazz.

"We didn't have that separation of church and state: You had to study Beethoven and Bach, Duke Ellington and Art Tatum. You had to study both worlds, the European classical music as well as the American classical music, which some people call 'jazz,'" Jamal told SFJAZZ Magazine.

Growing up, Jamal's musical idols were pianists Nat King Cole, Tatum, whom he met when he was 14, and especially fellow Pittsburgh native Erroll Garner. Asked about the source of his orchestral approach to his ensembles, Jamal replied: "Erroll Garner! They don't come any more orchestrated than Erroll. He's an orchestra within himself. He was my biggest influence."

Jamal began playing professionally at 14, toured with classmate George Hudson's big band at 17, and was signed to Okeh Records by producer John Hammond in his early 20s. He recorded a critically acclaimed album by the time he was 25. By the late 1940s, Jamal was married and living in Chicago, and seemingly determined to record every song in The Great American Songbook.

Jamal had an uncanny knack for deconstructing popular tunes and reassembling them in unexpected ways.

A two-disk release titled The Legendary Okeh and Epic Recordings brings together Jamal's recordings between 1951 and 1955, with guitarist Ray Crawford and bass players Eddie Calhoun and Israel Crosby.

As a teenager, Jamal listened to bebop artists like Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell and Charlie Parker but he chose a different path.

"Jamal ushered in a new era of melodic improvisation that stood in sharp contrast to bebop's previous innovations," wrote AllMusic critic Thom Jurek.

Check out Jamal's version of "Squeeze Me," with Crawford on guitar and Crosby on bass.

A nine-disc compilation titled The Complete Ahmad Jamal Argo Sessions 1956-62 consists of well over 100 songs from The Great American Songbook, along with some Jamal originals. Each tune is artfully conceived and carefully rendered by trios that included Jamal's longtime bassist Israel Crosby, along with drummers Vernel Fournier and Walter Perkins. Here's Jamal's take on Irving Berlin's "Cheek to Cheek" from The Complete Argo Sessions, with Fournier on drums and Crosby on bass.

Miles Davis and Gil Evans

Miles Davis and his arranger, Gil Evans, were early admirers. "All my inspiration comes from Ahmad Jamal," Miles acknowledged. "(Jamal) knocked me out with his concept of space, his lightness of touch, his understatement, and the way he phrased notes and chords and passages." Davis wrote in his autobiography. "Listen to the way Ahmad Jamal uses space," Davis said. "He lets it go so you can feel the rhythm section and the rhythm section can feel you. It's not crowded." Davis even encouraged his pianist, Red Garland, to "play more like Jamal."Drummer Jimmy Cobb, who was a good friend of Davis, told Billboard: "He listened to so much Ahmad Jamal. In fact, when he was in Chicago, he would go to the hotel where Ahmad Jamal was playing like every night. And if you listen to some of his first recordings, it had a lot to do with what he heard from Ahmad, in terms of tuning and conceptualizing the music and all that, and also played a part in (what we were doing in 1959) too."

Davis and Gil Evans covered Jamal's "New Rhumba" from his 1955 album, Chamber Music of the New Jazz, for their 1957 big band record, Miles Ahead (aka, Miles Plus 19). Although they never performed together, Jamal said he and Miles formed a "mutual admiration society."

Here's Jamal's trio's rendition of "New Rhumba" side by side with Miles and Evans' big band version. That's Israel Crosby on bass and the innovative Ray Crawford on guitar, making percussive beats with his thumb on the guitar fret before Jamal had a drummer.

The Embers Club

In 1956, Jamal's trio had a gig at The Embers Club playing during the headliner's intermissions. Though it didn't end well due to an unfortunate altercation between Jamal and a customer, the night was to have historic repercussions.Back in Chicago, Jamal replaced Crawford with coveted New Orleans drummer Vernel Fournier. Here's a video of that trio playing "Darn That Dream." Crosby is on bass, Fournier plays drums and Jamal is on the Steinway.

At the Pershing, But Not for Me

In early 1958, the Ahmad Jamal Trio stunned the music world with an album that was audaciously different from anything that had gone before it.Jamal was granted a long residency at The Pershing Lounge, a popular Black-owned club on the South Side of Chicago. Leonard Chess of Chess Records agreed to remotely record the shows. It was one of the best business decisions that Chess would ever make. The group painstakingly whittled the 43 songs they recorded at The Pershing down to eight and released the collection on Argo Records, a subsidiary of Chess, as Live at the Pershing, But Not for Me. Fortunately for Jamal and posterity, the sound, recorded on engineer Mal Chisholm's two-track machine, is very good for the period. The sublime opening track, "But Not for Me," sets the tone and shows off Ahmad's light, shimmering touch.

George Gershwin and Ira Gershwin wrote the song in 1930 for the musical Girl Crazy.

Poinciana-Mania

The album's unlikely breakout smash hit (except to Jamal, who knew it would be a hit) was "Poinciana," a Latin-tinged chestnut written in 1936 by Nat Simon, with lyrics by Buddy Bernier. It was featured in the 1952 movie Dreamboat. The song was widely covered by crooners and musicians during the 1950s. Listeners would have been familiar with Nat Cole's version of "Poinciana." (watch video). Along with Erroll Garner and Art Tatum, Cole was one of Jamal's musical idols.Jamal had recorded "Poinciana" before but completely revamped it at nearly double the length for At the Pershing. Since airplay was tightly limited, a shorter-version single was also released. To my untrained ear, what Jamal accomplished with his stunning version of "Poinciana" verges on musical alchemy. It begins with Fournier's beguiling New Orleans second-line drum pattern.

Poinciana

Some critics dismissed the record as "cocktail lounge music." (Artists can pay a heavy price if critics deem their music to be "too popular.") Nonetheless, the country was smitten with Jamal's version of "Poinciana," which was an overnight sensation. At the Pershing, But Not for Me opened as the #3 record on Billboard and remained on the charts for 108 weeks. It was the best-selling jazz album of 1958, according to Downbeat and to that point, the best-selling instrumental jazz record ever.People reportedly would visit record stores searching for At the Pershing, But Not for Me or the "Poinciana" single specifically, and only afterward would they peruse the rest of the jazz records. Ranking At the Pershing, But Not for Me at 21 in its list of the 100 best jazz albums of all time, Jazzwise wrote: "That it was no flash in the pan is shown by the music's drawing power and continuing fascination today, as well as its ability to influence every new generation of pianists." "We achieved the ultimate success," Jamal recalled. "I mean, we were selling so many records at one time, on the original At The Pershing album, that Leonard himself, the president, was in the stockroom shipping with the stock boys."

A Career-Altering Record

The impact that At the Pershing and "Poinciana" had on Ahmad Jamal's career was similar to what another instrumental jazz hit, "Take Five," did for Dave Brubeck a year later. Jamal had transcended his humble origins to achieve a degree of financial security. More importantly, from that point forward he would enjoy a rare degree of artistic freedom and creative independence throughout a career that spanned seven decades. The trio disbanded a few years after At the Pershing and Jamal took a hiatus in the early '60s. Earnings from At the Pershing allowed him to open a nightclub in Chicago called The Alhambra, where he presumably could perform without traveling.< Previous

Lisa Hilton: California-Based Jazz Pi...

Next >

Groove Junkies

Comments

Tags

Profile

Ahmad Jamal

Chuck Lenatti

At The Pershing / But Not For Me

Poinciana

Chess Records

Argo Records

Pittsburgh

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.